English 4 Test Questions and Answers

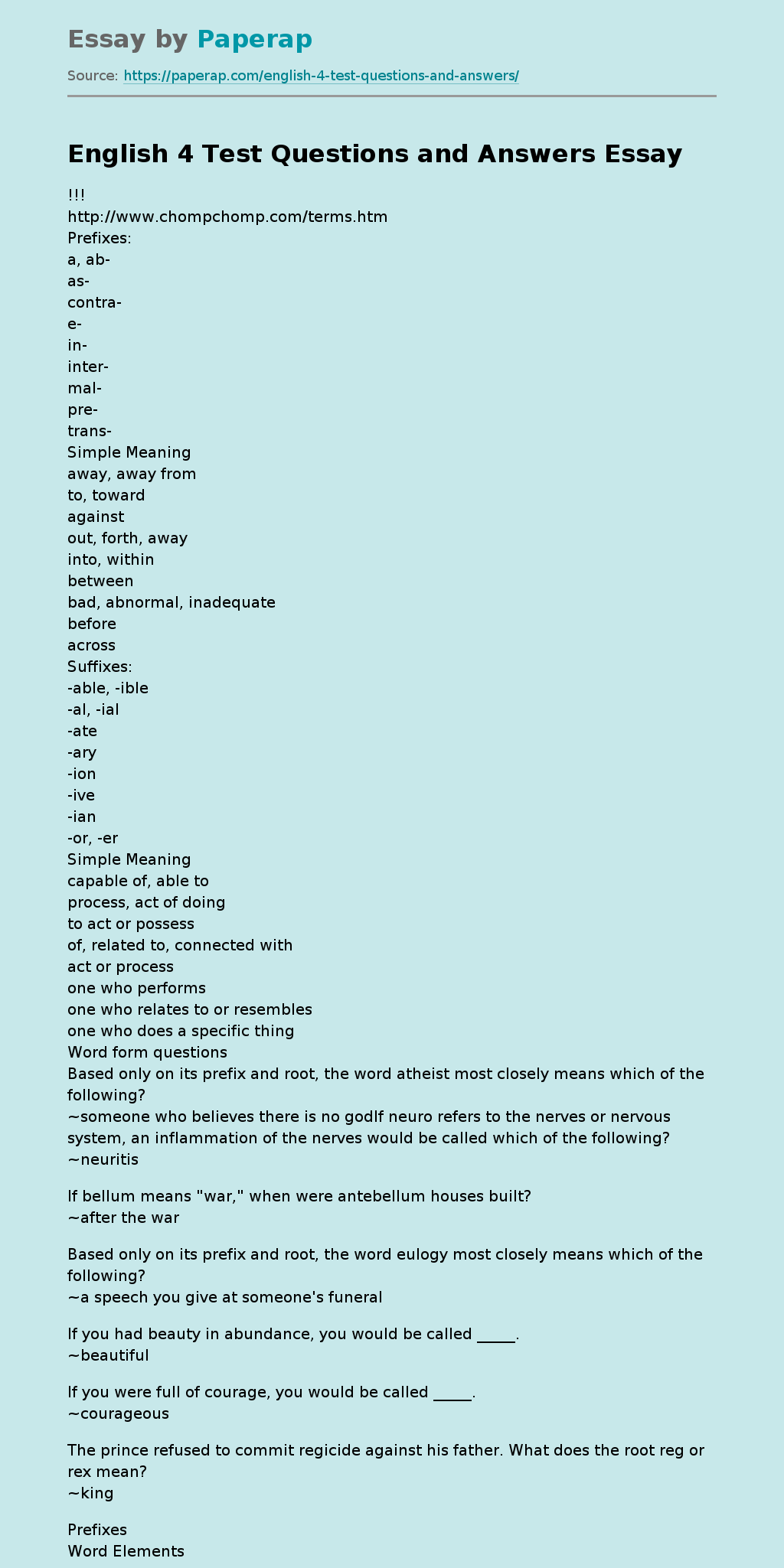

a, ab-

as-

contra-

e-

in-

inter-

mal-

pre-

trans-

away, away from

to, toward

against

out, forth, away

into, within

between

bad, abnormal, inadequate

before

across

-able, -ible

-al, -ial

-ate

-ary

-ion

-ive

-ian

-or, -er

capable of, able to

process, act of doing

to act or possess

of, related to, connected with

act or process

one who performs

one who relates to or resembles

one who does a specific thing

~someone who believes there is no godIf neuro refers to the nerves or nervous system, an inflammation of the nerves would be called which of the following?

~neuritis

If bellum means “war,” when were antebellum houses built?

~after the war

Based only on its prefix and root, the word eulogy most closely means which of the following?

~a speech you give at someone’s funeral

If you had beauty in abundance, you would be called _____.

~beautiful

If you were full of courage, you would be called _____.

~courageous

The prince refused to commit regicide against his father. What does the root reg or rex mean?

~king

Word Elements Meanings

a- not, outside of

per- through, thoroughly

anti- against

ante- before

eu- good

ex- out of, formerly

in- not

multi- many

Sample Words

atypical, amoral

perfect, permission, pertain

antibody, antisocial

anterior, antecedent, antebellum

eulogy, euphonious, eugenic

ex-president, exhume, excise

inhumane, indispensable, inadmissible

multicolored, multiform, multimillionaire

Word Elements Meanings

anthropo man

bio life

cide, cis to kill or cut

corps body

cosmos world, world system

log to study, the science of

logos word, reason, study

theo god or gods

Sample Words

anthropology, misanthropy, philanthropic

biology, biographical, autobiography

scissors, incisive, homicide

incorporate, corpse, corpuscle

cosmic, cosmonaut, cosmological

anthropology, biological, dermatology

logic, dialogue, prologue

theology, polytheism, atheism

Word Elements Meanings

-itis inflammation

-ful have in abundance

-ism doctrine or belief in

-ist one who believes

-ness quality or condition of

-ous possessing, full of

Sample Words

tonsillitis, appendicitis, sinusitis

plentiful, graceful, resentful

socialism, humanism, communism

Marxist, isolationist, optimist

weariness, loneliness, kindliness

contemptuous, advantageous, dubious

Word Element Meaning

arch ruler, beginning

astro star

cap to take, seize

cogn to know

derm skin

gam marriage

gen race or kind

gest to bear

gnos to know

graph to write

ject to throw

media middle

metro to measure

mon to warn

mort death

nasci to be born

neuron nerves

nym name

path sickness, feeling

pel, plus to drive

pli, plic to fold

pon, pos to put, place

port to carry

press to push

psych mind, behavior

rog to ask

scrib to write

socio society

soma body

sta, sti to stand

Example

monarch

astronomy

captive

recognize

hypodermic

monogamy

generation

gestation

agnostic

autograph

projection

median strip

metric system

admonish

immortality

renaissance

neurologist

antonym

pathology

impel

complicate

dispose

import

compress

psychology

interrogate

script

sociology

psychosomatic

stature

Word Element Meaning

auto- self

bi- two

com- with

con- against

de- down, away

dis- apart, not

homo- same

hyper- above, very

hypo- under, below

inter- between

iso- equal, similar

mono- one

o-, ob- against, away from

non- not

per- through, thoroughly

poly- many

pro- in favor of, before

re-, retro- back, again

un- not

sub- under, below

Example

automobile

bicycle

commit

contrary

detain

distend

homogenize

hyperactive

hypodermic

intermural

isometrics

monologue

object

nonacid

permit

polyglot

project

refer

unnatural

submit

Word Element Meaning

-ance, -ence condition

-ant, -ent one who acts or believes

-ize to make similar to

-ship status, function

-ive tends toward an indicated action

-ity quality

Example

importance

applicant

colonize

ownership

conductive

objectify

ven=to come

vers, vert=to turn

ten, tain, tend=to hold

mit, mis=send

cogon=to know

cap=to take, seize

sta, sti=to stand

pli, plic=to fold

duc=to lead

nym=nameThe suffixes -able and -ible mean “able to.

”

~true

Spectator comes from the Latin specs meaning _____.

~to look

Biography comes from two Latin words: bio meaning “*life*” and graph meaning “to *write*.”

What does the suffix -logy in the word astrology mean?

~study of

EX: COBOL = COmmon Business Oriented Language (a computer term)

FORTRAN =

FORmula TRANslation in data processing

laser = Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation

radar = RAdio Detecting And Ranging

RSVP = Respondez S’il Vous Plait–French for “Please respond”

scuba = Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus

TVA = Tennessee Valley Authority

ZIP = Zone Improvement Program–for speeding the mail

NOT: Mr., Mrs., Sat., Feb., Dr., Hon., and the like.

2. barometer

3. basso profundo

4. bells

5. cuisine

6. cymbal

7. dome mountain

8. igneous

9. maitre d’

10. metamorphic

11. sedimentary

12. texturing

13. vertebrate

2. an instrument for measuring air pressure

3. a deep bass voice that extends to C below bass staff

4. percussion instruments consisting of metal bars or tubes

5. manner of preparing food

6. a concave brass plate that produces a brilliant clashing tone

7. a natural formation that resembles a dome

8. formed by solidification of molten magma

9. headwaiter, a shortened form of maitre d’ hotel, literally master of the house

10. referring to a pronounced change caused by pressure, heat, and water that results in a more compact and more highly crystalline condition

11. formed by or from deposits of sediment

12. the application of a plaster-like product over wallboard in a manner that produces a different look

13. an animal having a spinal column in contradistinction to an invertebrate, an animal that does not have a spinal column

EX: 1. construction – footing, stem wall, monolithic pour, mud, rebar, etc..

2. chefs – hors d’oeuvres (or dervz), bouillon, chef’s salad, entree, etc..

3. firefighting – catching a plug, turnouts, stinger, fog hog, surround and drown a fully-involved, etc..

4. medicine – heterotropia, stethoscope, heterotropia, morbilli rubeola, halitosis, etc..

5. geology – igneous, sedimentary, metamorphic, dome mountain, barometer, etc..

6. biology – invertebrates –> arthropods, arachnids, crustaceans, centipedes and millipedes

vertebrates –> birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, mammals

7. literature – personification, onomatopoeia, foreshadowing, plot, dramatic conflict, theme, character delineation, immediacy, atmosphere, a point of view, limited focus, unity, etc..

8. music – soprano, mezzo soprano, contralto, alto, tenor, second tenor, baritone, bass, etc..

~morbilli rubeolaAn ophthalmo-orhinolaryngololist is _____.

~an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist

Heterotropia is _____.

~cross-eyes

Which is not a class of rock?

~disturbed

What is the study of weather is called?

~meteorology

When we speak of inanimate objects as if they were human, what are we using?

~personification

What is a type or classification of writing in literature called?

~genre

What is the main character in a short story called?

~protagonist

Who directs an orchestra?

~both conductor and maestro

1. classification/division – grouping a small selection of items into categories

2. causal analysis – describing cause and effect

3. process analysis – analyzing a process such as how to scramble eggs or how to play basketball

4. illustration or example – defining or clarifying a concept or type by use of examples/illustrations

5. comparison/contrast – considering similarities, differences, or both

6. extended definition – analyzing the term to be defined, its class, and various distinctive characteristicsChoose how the following paragraph could be best classified:

1. Movie rental stores offer great variety that appeals to even the choosiest of patrons. Action movies fill the need for adventure and adrenaline rush. Comedies help people to laugh and just have fun. Romantic movies offer a view into what matters to just about everyone–love. *classification/division*

2. Philip stayed up too late reading an exciting novel. The next morning, he overslept and arrived late at school. He stuttered while giving his history report and dozed off in his afternoon math class. Philip went to bed early the following evening, to be sure. *causal analysis*

Which of the following limited topics would be appropriate for a short paper?

~The influence of Elvis on Rock

~How Mia Hamm revolutionized soccer

~In most American homes, family time *is replaced with TV time.*

~Chuck *is a hard-working father.*T/F: The subject of the topic sentence is called the controlling idea.

~false

T/F: The controlling idea is in the predicate of a topic sentence.

T/F: The controlling idea should be in the main clause of the topic sentence.

T/F: The subject of the topic sentence is called the controlling idea

true

false

-the complete verb by itself is called the simple predicate

-the complete predicate is the part of the sentence that says something about the subject and is made up of the verb and its complement with or without modifiers

EX: Jill ate the broken cookie.2. *compound sentence* – sentence that has at least two main clauses or two simple sentences; these clauses are connected either by a comma and a coordinating conjunction–and, but, or, for, nor, yet–or by a semicolon. If any other connecting word is used, a semicolon is still required.

EX: I chose a blue bicycle, *but* my brother wanted a red one.

He dropped out of class early in the year; none of us knew why.

3. *complex sentence* – having a main clause and one or more subordinate clauses

4. *compound-complex sentence* – is one that has two or more main clauses and one or more dependent or subordinate clauses.

EX: When I saw the dark clouds in the distance, I left the picnic quickly, and I took Stephanie home in my car.

Since the expressway was built, very few tourists have visited our town. – complex sentence

If it takes as long to explore the moon as it did to explore this continent, our generation will not live to see the job finished. – complex sentence

Making important decisions requires time for careful thinking and courage to take action. – simple sentence

When you can see both sides of an issue equally well, you find it difficult to take a stand, but some people insist that you take one side or the other. – compound-complex sentence

The first milestone in lighting may have occurred when early man lit a torch from his cooking fire. – complex sentence

He went up the stairs, and there he confronted the thief. – compound sentence

While I was standing in the doorway, I was protected from the rain. – complex

Informality is sometimes fine; however, it can be carried too far. – compound

They were lovely people, the kind you might meet anywhere. – complex

I love this study, and I am going to continue in it. – compound

EX: burned, burnt

-*past perfect tense* : action completed before a set time in the past (or before another past action)

EX: burned, burnt

-*present tense* : action happening now, this minute, today

EX: burn, burns

-*present perfect tense* : action completed during the present time (past action at any time before now)

EX: burning

-*future tense* : action expected to happen

EX: will burn

-*future perfect tense* : (seldom used) action completed before a set time in the future

EX: I will/shall have chosen

Past: froze

Present Participle: freezing

Past Participle: frozentear

Past: tore

Present Participle: tearing

Past Participle: torn

kick

Past: kicked

Present Participle: kicking

Past Participle: kicked

~Italics are used with the titles of long works.

~Foreign words not in mainstream use in the English language (these words are indicated in many dictionaries with an asterisk (*).

EX: corpus juris, corrida

~names of ships, trains, aircraft, and titles of famous paintings

~Words, letters, or figures used as such and words used as words are italicized.

EX: The articles are *a, an,* and *the.*

– In England, a run in a stocking is called a *ladder.*

– In the English language a *q* is never used without a *u* in a word.

– You have four *and’s* in one sentence,

– My social security number has three *7’s* in it.Using *quotation marks*:

~Titles of short works

~poetry, short stories, short plays, and chapter titles in books

*Abbreviations*

~When writing a formal essay generally avoid abbreviations, with a few will-known exceptions:

Mr., Messrs., Mrs., Mmes., Dr., and St. (for saint, not street) These titles are spelled out when they are not followed by a proper name.

~The title Honorable may be abbreviated to Hon. only if the first name or initials are used

~In an essay the names of states, countries, months, days of the week, the words Road, Park, Street, or Company are abbreviated when they are part of a name, not otherwise. Using abbreviations in an address on an envelope is acceptable.

~Avoid the use of the abbreviation for and, the ampersand (&)

~Avoid abbreviations of people’s first names such as Wm., Jas., Chas., Geo., and any other first name abbreviation. Spell out such proper names.

~Acronyms may be used instead of writing out the entire title of an organization if the acronym is explained the first time it is used. GOP means Grand Old Party but refers to the Republican Party.

~After proper names, titles earned or awarded are expressed in abbreviations: Jr., Sr., Esq., and degrees such as Ph.D. (Doctor of Philosophy), M.A. (Master of Arts), M.D.(Doctor of Medicine), R.N.(Registered Nurse), D.O. (Doctor of Osteopathy), P.A. (Physician’s Assistant).

~Abbreviations may be used with dates or numerals:

A.D. (anno Domini or “in the year of our Lord”)

B.C. (before Christ)

A.M. and P.M. or a.m. and p.m.,

No. and $.

~The following sentence situations allow for abbreviations:

The manuscript was dated to 783 B.C.

He was to arrive at 10:30 A.M.

The detective found the gun in room No. 266.

I received a check for $585.00

~Some Latin abbreviations are used in formal writing, but one never makes a mistake by spelling out such expressions:

e.g. (for example)

viz. (namely)

i.e. (that is)

cf. (compare)

etc. (and so forth)

*Using Numbers*

~Numbers that can be expressed in one word (including hyphenated words) are written out unless a series of numbers is to be used, and/or if some of the numbers require two or three words. In such cases use Arabic numerals for all of the numbers

EX: The house was 75 feet long and 30 feet wide; the lot upon which it sat was 205 feet wide and 80 feet deep.

~Ordinal numbers (those numbers which express position and end in -st, -rd, end, -th) may be written out or expressed in figures. However, such endings should not be added to the day of the month when the year follows.

EX: Acceptable: January first; the eighteenth of June, or the 18th of June

Unacceptable: January first, 1897; June 18th, 1978

~Use figures for street numbers, pages, decimals, percentages, and for the hour of the day when used with A.M. or P.M.

EX: 148 Westwood Drive; 232 Fancher Boulevard

The plane leaves at 4:55 P.M.

Canyon Savings pays 5 1/2 percent compounded daily.

The poem may be found on page 97.

The coat cost $79.95.

*Capitalization*

~Capitalize proper nouns, which include names of specific people, places, regions, days of the week, historical periods, months (but not seasons), ships, organizations, and religions

~Copyrighted names of products should also be capitalized, however, in some cases a proper name has become a generic term

EX: India rubber, guinea pig, osterizer, vulcanize, pasteurized

~Titles are capitalized only when used with names:

EX: Captain Roberts, Nurse Renwick, Dean Joshua

~Names indicating family relationship when they are not accompanied by a *possessive* are capitalized: Mother made the pie.

EXCEPTIONS: my mother, his father, etc.

~Points of the compass are capitalized when referring to a place: the Southwest, the Near East…

~Always capitalize the names of languages and of specific classes: Humanities 101, Freshman Composition II…

~error concerning abbreviationsBy 7: 20 P.M., only 7 tickets were left.

~error involving numbers

John is a Doctor who does not make house calls.

~error concerning capitalization

3 days of our holiday are left to enjoy.

~error involving numbers

Doctor White teaches literature 328, which is a very interesting course.

~error concerning capitalization (Literature, because it is a specific course)

Sue acts on the belief that a dollar earned is a dollar spent.

~no error

Dr. Thomas Jones lives on East Main Street.

~no error

Find the sentence with no capitalization errors.

-In high school, I’m learning English, speech, and Latin.

-Edgar Allan Poe, the American poet, was adopted.

-In New Hampshire, Mother starred in The Tempest.

-Is your aunt a professor of German at Penn State?

-We heard that Dr. Smith was the only physician to receive the Nobel Prize.

-Many people go to Page, Arizona, to ride a Colorado River raft.

One class’s attitude

the baby’s toy

the ox’s yoke

the bus’s emission

the man’s hat

the sheep’s woolOne exception governs proper names that end in s. Although it is not incorrect to add the ‘s, common practice simply adds the apostrophe to such names.

EX: Phyllis’ coat

Charles’ car

Mr. Jones’ office

PLURAL POSSESSION has two rules:

-If the plural form of the noun ends in s, add the apostrophe behind the existing s.

-If the plural noun does not end in s, add ‘s.

EX:

the chairmen’s decision

the ladies’ club

the deer’s tails

the companies’ agreement

the oxen’s yokes

the Joneses’ house

Select all that apply.

The ” s verb” occurs in _____.

singular

present tense

indicative mood

When a comma is used alone to combine two or more sentences, the error is called a comma splice-Incorrect: It rained for two hours today, the children played in the puddles till dark.

-Correct: It rained for two hours today, and the children played in the puddles till dark.

-Incorrect: Come to see me soon, we need to talk.

-Correct: Come to see me soon; we need to talk.

*fused sentence or a fusion*

A second type of run-on sentence occurs when no punctuation appears between two main clauses.

-Incorrect: His parents are professional people they are both doctors.

-Correct: His parents are professional people; they are both doctors.

-Incorrect: Put the groceries on the kitchen table then come into the living room.

-Correct: Put the groceries on the kitchen table; then come into the living room.

occurs, for example, when you move from present tense to past and back to present again for no good reason.

EX: Mr. Firman *invited* his friend to come over and have dinner. The maid *fixes* a big dinner for them, and when they were ready for dessert, she *brings* a cake out for Mr. Nulty because it *was* his fifty-ninth birthday…2. Shift in PERSON:

refers primarily to the use of the personal pronoun. You remember that:

~first person relates to the person speaking

~second person refers to the person being spoken to

~third person pertains to the person or persons being spoken about

As applied to writing, consistency in person is the principle that once a writer begins using one person, he or she will not shift to another person. Consider the following example, taken from the paragraph example discussed earlier in the lesson.

EX: Every step *you* make reminds *you your* life depends on surefootedness, not foolhardiness. Every climber must carefully check over *his and his* teammates’ equipment, inspecting it for faults which might later cause it to fail.

3. Shift in NUMBER:

1. “We find that in judging *people*, we overlook

most of the characteristics that draw us to *him*.”

2. “Conclusions about a person by misjudging *their* facial expressions…”

3. “They judge a *person* incorrectly because they fail to see *them* as *they* really are.”

All three sentences above contain problems of pronoun-antecedent agreement.

To summarize, a pronoun must agree in person, number, and gender with its antecedent.

4. Shift in VOICE:

not as noticeable as other shifts. Most writing is done in the active voice where the subject does the acting. In the passive voice, the subject receives the action of the verb.

The passive voice has two valid uses:

~When the actor is not known, he cannot very well be mentioned. If a bank has been robbed, and the robbers have not yet been apprehended, the newspaper cannot come out with an active voice statement. The best it can do is say that “The Calley National Bank on Poe and Wentworth was robbed of $75,000 at closing time yesterday.” That sentence construction represents the best possible method of telling what is known.

~When the actor is not important, a statement would read like this: “The new wing on the Community Hospital has been completed.” Surely the completion of the building is more important than the fact that Cominskey Brothers Contracting Company did the work.

A shift from active to passive voice, then, is unwise only when it is unnecessary. A report written in the passive voice is cumbersome and lacks sparkle because all of the subjects are acted upon.

The following piece of writing probably overdoes the point, but notice the deadening affect achieved by the passive voice:

EX: Vows were taken at St. James Cathedral by Bonnie Eager and Jerry Wrightman. The bride’s dress was made by the bride. At the reception, punch was drunk and cake was eaten while the bride and groom were greeted by their friends. The bride’s bouquet was thrown by the bride and was caught by her sister. Rice and confetti were thrown by the excited crowd as the bride and groom were whisked away by a well decorated car which was driven by the best man. Tears were shed by the mother of the bride while hats were thrown into the air by the brothers of the groom. A good time was had by all.

Select all that apply.

Which kinds of shifting upset the viewpoint in an essay?

shift in person

shift in tense

What part of speech is the italicized word in the sentence below?

Four *score* and seven years ago, our forefathers brought *forth* *upon* this continent a new nation conceived in *liberty* and dedicated to the proposition *that* all men are created equal.

forth – adverb

upon – preposition

liberty – noun

that – pronoun

are naming words such as car, horse, school, Frank, Colorado River, safety, and love–words that we use primarily to stand for things, animals, places, people, and ideas. The tangible objects are called concrete nouns. Thought processes, ideas, or other intangible things, including hatred, sovereignty, and devotion are called abstract nouns.

Nouns normally have a separate form for the singular and for the plural. They also take inflectional endings for showing ownership or possession.

Select all that apply.

Which sentence elements can be used as nouns or noun substitutes?

gerund

noun clause

Which of the answers is not a noun in the sentences below?

We will have to learn to think for ourselves. This process will be difficult, but without it, we will be little more than puppets. Nobody wants that.

~who, whom, whose, which, that

~function: to introduce dependent (adjective) clauses*interrogative pronouns*

~Who?, Whom?, Whose?, Which?, What?

~function: to ask questions

*demonstrative pronouns*

~this, that, these, those

~function: to point out

*reflexive pronouns*

~myself, yourself, himself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves

~function: to reflect or intensify

*indefinite pronouns*

~(singular) one, anyone, someone, no one, none, everyone, anybody, somebody, nobody, everybody, anything, something, nothing, everything, much, either, neither, another, (plural) many, all, others, few, several, some, most

~function: to stand for an unnamed antecedent (indicates an unspecified person or thing)

*personal pronouns*

~function: to take the place of nouns naming people or things.

(singular 1st, 2nd, 3rd person, plural 1st, 2nd, 3rd person)

~cases of personal pronouns include nominative, objective, 2 possessive cases

is used for direct objects, indirect objects, and objects of prepositions

Which of the following is not a function of an objective pronoun?

subject complement

Pronominal adjectives include

*my, your, his, her, its, our, your, and their*

These words take the place of possessive nouns like Bill’s, the crowd’s, Mother’s, etc. and describe whatever the original possessive nouns describe.EX: John’s keys are in Sally’s car. His keys are in her car.

Both his and her stand for possessive adjectives, in this case, the possessive words John’s and Sally’s. His and her also describe the nouns keys and car.

2. *independent possessives* : these words are “independent” because each can replace an entire possessive noun phrase, not just part of one. Inpendent possessives include

*mine, your, his, hers, its, ours, yours, and theirs*

EX: Those keys are my keys. Those keys are mine.

That car over there is her car. That car over there is hers.

mine replaces the possessive noun phrase my keys and takes on its function of subject complement. The same thing happens in the second example. Hers takes the place of the possessive noun phrase her car.

Notice that the possessive personal pronouns have no apostrophes because their only function is to indicate possession (i.e. their form never needs to change).

themselves – reflexive

this – demonstrative

those – demonstrative

what – interrogative

someone- indefinite

that (introduces dependent clause) – relative

we – personal

myself – reflexive

anybody – indefinite

When she came in to see a spilt soda pop on the papers she was grading, Mrs. Shore shrieked, “*Whose* drink is this?!” – interrogative

When Ian proudly retrieved his Calculus 2 homework and saw that it was covered with glue and glitter, he was horrified. His mind raced as he wondered who could be guilty of this sabotage. Suddenly, he knew. It could be *nobody* else but Melissa, his two year-old sister. – indefinite

When Amanda picked up Rosario’s cell phone by accident, Rosario kindly said, “I think *that* is mine.” – demonstrative

Seth Earwig, *who* was a self-proclaimed expert, continued his career as an alligator wrestler until he was eaten one November morning. –

relative

continue to be used today in the literary context of Shakespeare and other important 17th and 18th century works of literature.

The 6 tenses are: present, past, future, preset perfect, past perfect, future perfect (described in definition of “terms”)Verbs form the tenses listed above using the four principal parts. Verbs are classified as regular or irregular by the way they form their principle parts.

-Regular verbs form their past and past participle by adding *-d, -red, or -t to the present part.*

-Irregular verbs have no pattern or set inflections for forming their past and past participles. Be is the most irregular form in the language and has eight forms: am, is, are, was, were, be, being, been.

all forms of a verb (both regular and irregular) are made from these forms

1. *present part* : is used with will and shall to form the future tenses.

*Present* + will or shall = *future tense*

write + will or shall = will write

walk +will or shall = will walk

2. The *present participle part* is used with a “be verb” to form the progressive tense.

*Present participle* + “be verb” = *progressive tense*

writing + “be verb” = is writing, are writing, etc.

walking + “be verb” = is walking, are writing, etc.

3. *past part* : is used by itself to form the simple past tense.

4. The past participle part is *used with the auxiliaries* “have, has, or had” to form the present perfect and past perfect tenses. The past participle is also used with a “be verb” to form the passive voice.

*Past participle* + have, has, or had = *past/present perfect tense*

written + have, has, or had = has/had/have written

talked + have, has, or had = has/had/have talked

*Past participle* +”be verb”= *past/present perfect tense*

written + “be verb” = is/was/has been written

played + “be verb” = is/was/has been played

~Hearing the fire siren, I pulled over to the side of the road.2. The lawyer asked many questions. *He was determined to get to the truth.* (past participial phrase)

~The lawyer asked many questions, determined to get to the truth.

3. *The police inspector looked for evidence.* He examined the apartment thoroughly. (present participial phrase)

~Looking for evidence, the police inspector examined the apartment thoroughly.

4. *The boardwalk is closed for the winter.* It is a depressing sight. (past participial phrase)

~Closed for the winter, the boardwalk is a depressing sight.

5. Nate is active in sports. *He plays both football and baseball.* (present participial phrase)

~Nate is active in sports, playing both football and baseball.

Participle/participial phrase: Hearing his name called

Noun or pronoun modified: Travis2. Anything connected with basketball interests me.

Participle/participial phrase: connected with basketball

Noun or pronoun modified: Anything

3. Roasted in aluminum foil, meats remain juicy.

Participle/participial phrase: Roasted in aluminum foil

Noun or pronoun modified: meats

4. All people crossing into Arizona must prove they are not carrying fruits or plants.

Participle/participial phrase: crossing into Arizona

Noun or pronoun modified: people

5. Cradled in her mother’s arms, the baby slept.

Participle/participial phrase: Cradled in her mother’s arms

Noun or pronoun modified: baby

6. Storms, injuring crops and destroying property, pounded the California coast.

Participle/participial phrase: injuring crops and destroying property

Noun or pronoun modified: storms

7. The covered bridge was picturesque.

Participle/participial phrase: covered

Noun or pronoun modified: bridge

8. A person observing a crime should call Crime Stop.

Participle/participial phrase: observing a crime

Noun or pronoun modified: person

9. Seen by two women, the accident was reported immediately.

Participle/participial phrase: Seen by two women

Noun or pronoun modified: accident

am, are, is, was, were, be, been, being (the verb to be)

have, has, had (the verb to have)

do, does, did (the verb to do).The other auxiliaries can be used only as auxiliaries and are called *modals*:

can, could, shall, should, will, would, may, might. must.

Certain auxiliaries can combine together and “stack” on the main verb to form a verb phrase.

EX: Dorothy should certainly have been found by now.

Notice that three auxiliaries should, have, and been work together with the main verb found to create the complete verb phrase.

A sample conjugation for the present progressive tense in *active voice*:

I am choosing, we are choosing

you are choosing

she is choosing, they are choosingIn the *passive voice* this conjugation would be:

I am being chosen, we are being chosen

you are being chosen

she is being chosen, they are being chosen

1. *transitive verbs* are verbs taking a *direct object*Thick dust *covered* the desk. (“desk” is the receiver of the action “covered”)

They *designated* a hitter.

The clock *struck* one.

I *want* candy.

He *carried* the bag.

Jose *thanked* Wayne.

2. *intransitive verbs* are other action verbs *do not take a direct object*

Doris scowled. (Nothing in the sentence is being “scowled.”)

He *ran.*

They *napped.*

The dog *barked.*

Blair *gloated.*

Clarissa *winked.*

Sentences containing transitive verbs are either in active or passive voice.

1. *Active voice* means that the subject is performing the action of the verb.

EX: John finished his mid-term report. (John is performing the action of “finish”)

2. *Passive Voice* means that the subject is receiving the action of the verb.

EX: The report was finished (by John)

In the examples above, notice that the passive sentence says the same thing as the active sentence. However, the direct object of the first sentence, report, has become the subject of the second sentence. In either case, report still receives the action of the verb.

T/F: Transitive active and transitive passive sentences both have a receiver of the action.

T/F: A sentence containing an intransitive verb has a indirect object.

In the _____ voice the subject acts, but in the _____ voice, the subject receives the action.

false

active; passive

~type of verb: activeExperiments were conducted to try to teach Chimpanzees sign language.

~type of verb: passive

One chimpanzee showed signs of learning by his imitations.

~type of verb: passive

No innovative communication signals were produced by the chimpanzees

~type of verb: passive

Conjugate

1. “to know” in the ACTIVE VOICE using the future perfect tense.

I – will have known

You – will have known

He/She – will have known

We – will have known

You (plural) – will have known

They – will have known

2. “to fly” in the PASSIVE VOICE using the present perfect tense.

I – have been flown

You – have been flown

He/She – has been flown

We – have been flown

You (plural) – have been flown

They – have been flown

-lie and lay

-sit and set

-rise and raise

To understand these verbs better, you need to remember that some verbs indicate action that must be received; these verbs are called transitive verbs. Others verbs do not indicate action because they are not action verbs or because they do not require a receiver. These verbs are called intransitive, not transitive. The dictionary indicates v.t. for verb transitive or v.i. for verb intransitive.Infinitive Form / Present Participle / Past Participle / Present Participle / Past Participle

v.i. to lie / lie(s) / lay / lying / lain

v.t. to lay / lay (s) / laid / laying / laid

v.i. to sit / sit(s) / sat / sitting / sat

v.t. to set / set(s) / set / setting / set

v.i. to rise /rise(s) / rose / rising / risen

v.t. to raise / raise(s) / raised / raising / raised

The confusion with lie and lay results from the fact that the past tense of lie and the present tense of lay are the same form–lay.

*Intransitive* / *Transitive*(must have direct object)

Forms of lie / Forms of lay

Today I lie in bed. / Today I lay the book down.

Yesterday I lay there. / Yesterday I laid the book down.

I have lain in bed a week. / I have laid every book in place.

Forms of sit / Forms of set

I sit down to eat. / I usually set that book on the shelf.

We sat on the sofa. / You set it on the floor.

He has sat in that chair for years. / You have set that book there for the last time.

Forms of rise / Forms of raise

My mother rises at dawn. / I raise my right hand when I swear to tell the truth.

Yesterday, she rose later. / The boys raised their hands.

The price has risen. / He has raised the flag in honor of the veterans.

The key to avoiding confusion is *remembering which verb is transitive and which is intransitive. *This means that *you raise, set, or lay things to or in their proper places; however, you must lie, or sit, or rise somewhere or sometime.*

EX: Mr. Gray _____ his hat in the place where Don usually ___.

-Mary ___ down because her temperature had _____.

-Sally ___ the food on the counter to cool while she ______ the blinds.

-laid; sat

-lay; risen

-set; raised

*Indicative Mood* states an actuality or fact

-We will go to see a movie this Sunday.

-I’ll follow you.All present tense, third person, singular, indicative verbs in the English language end in s and are called “s verbs.” Notice the pattern:

I go, you go, he goes;

I study, you study, he studies;

I build, you build, she builds;

I swim, you swim, she swims

*Imperative Mood* makes a request; deals with desires, wishes, or conditions that do not exist

-Let’s go to see a movie this weekend!

-Please stop bugging me!

*Subjunctive Mood* expresses a doubtful condition (contrary to fact) and is often used with an “if” clause.

-If I were you, I wouldn’t buy a house.

-I wish I were more organized.

~mood of verb: subjunctive*Be* on time!

~mood of verb: imperative

All of the students *arrived* on time.

~mood of verb: indicative

If I were you, I would take advantage of the extra time you have.

~subjunctive

Use your time wisely.

~imperative

He uses his time wisely.

~indicative

do not show action, but instead, link the subject with a modifier in the predicate which describes or renames the subject. These verbs are called linking verbs and the words which they link to the subject are called subject complements (also called predicate nouns/adjectives).

EX: Doris is a cosmetologist. (“Is” links “Doris,” the subject, to the predicate noun “cosmetologist.”)

Doris is very busy. (“Is” links “Doris,” the subject, to the predicate adjective “busy.”)

common ones:

become, seem, appear, remain,

stay, turn, prove, grown,

emerge, continue, get, smell,

taste, sound, look, feel

T/F: A sentence containing a linking verb also has a predicate noun or predicate adjective.

The subjective complement comes after a(n) ______ verb.

linking

~type of verb: intransitiveThe snow covered the stacks of hay bales.

~type of verb: transitive

The old barn timbers creaked under a weight of snow.

~type of verb: intransitive

The winter scene was mysterious.

~type of verb: linking

-Complements are completers of thought. They serve as words or groups of words that complete the sense of the verb, the subject, or the object

-Possible complements include direct objects, indirect objects, subject complements (predicate nouns/adjectives), and object(ive) complements. The direct object and the subject complement are completers of the sense of the sentence. The direct object receives the action of the verb while the subject complement restates or describes the subject.

Select all that apply.

Which sentence elements can be used as modifiers?

infinitive

participle

adverb

direct object

other options:

adjective

adverb

conjunction

interjection

preposition

pronoun (above)

verb (above)

They are formed when you add suffixes like -al, -ish, -ive, -ly, -like, and -ous to nouns.The most common adjectives are *the articles a, an, and the.* Sometimes called determiners, these words predictably “point out” nouns.

Although adjectives usually precede the nouns they modify, an adjective can be used after a linking verb as a *predicate adjective* (subject complement).

He is a delightful companion. (pre-noun modifier)

He is delightful. (predicate adjective)

In rare instances, adjectives can modify pronouns:

-Jody knew one day she would find that *special* someone in whom she could confide.

-Jody knew one day she would find someone *special* in whom she could confide.

In both examples, special modifies the indefinite pronoun someone even though the second example shows the adjective following the pronoun.

T/F: Adjectives modify nouns, pronouns, and other adjectives.

T/F: The suffixes -al, -ly, and -ous , when added to nouns, turn those nouns into adjectives.

true

They are formed when you add -ly to adjectives-No modifiers: Sadie wrote letters.

-Adjective modifiers: Sadie wrote *several long* letters.

-Adverb modifiers: Sadie *carefully* wrote several *extremely* long letters.

Adverbs can be divided into three basic types, based on their meanings:

1. *Manner* – tells how, how much, or to what degree something is done (-ly adverbs)

2. *Place* – tells where something is done

3. *Time* – tells when something is done

Adverbs can answer the questions:

How?

When?

Where?

How often?

To what degree?

To use these questions, simply find the main verb and then use the verb with a question word.

T/F: All adverbs end in -ly.

T/F: Adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, and other adverbs.

T/F: Adverbs ending in -ly indicate how or how much.

T/F: Adverbs tell when, where, how, and why.

true

true

true

are function words that do not have inflections. They show the relationship between the object of the preposition, usually a noun or pronoun, and some other word in the sentence. A prepositional phrase always begins with the preposition and ends with the object; it may have many modifiers in between.

COMMON PREPOSITIONAL WORDS

against, before, down, on, to,

about, behind, during, over, until,

above, between, except, out, up,

across, beside, for, onto, unto,

along, besides, from, of, upon,

as, but, in, off, under,

at, below, into, since, underneath,

around, beneath, inside, through, with,

among, by, like, throughout, within,

amid, concerning, near, toward, without,

after

A prepositional phrase is *almost always used as a modifier*–either an *adjective phrase* modifying a noun or pronoun or an *adverb phrase* modifying a verb or an adjective. A prepositional phrase usually follows the word it modifies.

ex: The tiny mouse crept (*through* the round hole) (*in* the wall).

The example above contains both kinds of phrases. “Through the round hole” is an adverb phrase describing where the mouse crept. “In the wall” is an adjective phrase describing which hole the mouse crept through.

a word which links words, phrases, or clauses of the same type

One group of conjunctions are called the *coordinating conjunction* which includes:

and, but, or, for, nor, yet, and sometimes so.

These conjunctions connect words, phrases, or clauses of same type.

*Subordinating conjunctions* include:

after, although, when, where, while, since, because, until, and many others–are used to connect subordinate clauses to main clauses

sudden feeling. Any part of speech may be used as an interjection.

Ouch! Oh! Stop! Wait! (verbs)

Great! (adjective)

No! (adverb)

But! (conjunction)

Ugh! Yow! Eek! (words representing sounds)

An interjection may be a single word or a phrase. In either case, an interjection is punctuated like a sentence.

1. Declarative Sentence – indicative statement

2. Imperative Sentence – request or command

3. Exclamatory Sentence – exclamation

4. Interrogative Sentence – question

Most basic sentence pattern indicating word order.

EX: S-V: The drowning man was rescued (by the lifeguard).

S-V: Jessie scowled at the pestering salesman.

The verb in the S-V pattern is intransitive-active because there is no object. There is a prepositional phrase following the verb, but its pattern is still S-V. In the sentence, Joe ran, Joe, obviously the subject, is in the nominative case.2. *Subject-Verb-Direct Object pattern*

EX: S-V-DO: John sees Mary.

expanded: My brother John sees his cousin Mary.

S-V-DO variation: subject-verb-direct object-objective complement (S-V-DO-OC): We elected John president.

The verb in the S-V-DO pattern is transitive-active because the sentence has a direct object.

3. *Subject-Verb-Indirect Object-Direct Object pattern*

EX:S-V-IO-DO: Mr. Miller bought his wife flowers.

S-V-IO-DO: (You) Give me the ticket for the show.

Again, the presence of a direct object in this sentence causes the verb to be transitive-active.

4. *Subject-Linking Verb-Predicate Noun pattern*

EX: S-LV-PN: Most (of my friends) have become teachers.

Because there is a linking verb in this sentence, teachers is the predicate noun.

5. *Subject-Linking Verb-Predicate Adjective pattern*

EX: S-LV-PA: The mountain retreat is extremely peaceful.

This sentence also contains a linking verb, but it has an adjective in the predicate, peaceful

6. *Inverted Sentence pattern: expletive-verb-subject*

EX: E-V-S: There are many people in the audience.

E-V-S: Here is my answer to your question.

Remember that here and there are never subjects in a sentence, even when they begin the sentence.

EX: Does Bill know that?

Are your problems produced by your own mistakes?Verb-There-Subject

EX: Are there any questions?

Is there a doctor in the house?

Auxiliary-There-Verb-Subject

EX: Can there be any peace?

Could there be any hope?

Direct Object-Auxiliary-Subject-Action Verb

EX: What did your mother plan (for your birthday party)?

Which plan (of mine) will you accept?

Adverb-Auxiliary-Subject-Action Verb

EX: Where are you going?

Why did Marcie wear that odd shirt?

Relaxing under a shady tree is very pleasant. -S-LV-PA

The waterfall rushed down the steep hillside. – S-V

Snow skiing is a very exciting sport. – S-LV-PN

The President sent the ambassador an invitation to the meeting. – S-V-IO-DO

There is good reason to be thankful. – E-V-S

answer the questions What? or Who(m)? after the verb

-A direct object is a noun or noun substitute that comes after an action verb

-a subject complement may also be a noun or noun substitute (predicate noun), or it may be an adjective (predicate adjective). Subject complements follow linking verbs.

T/F: A subject complement cannot be a noun substitute.

The direct object comes after a(n) _____

The objective complement comes ____ the direct object.

action

after

!!!!!The indirect object always comes _____ the verb and the direct object.

The ________ answers the question “to or for whom?”

indirect object

verbal with its complement and/or any modifiers

EX:

*Sleeping quietly in its crib*, the baby twitched as though dreaming.(participial phrase–used as an adjective)

*Sleeping at least eight hours per night* is an essential part of maintaining the body’s health. (gerund phrase– used as a noun subject).

I need *to sleep for six hours without waking.* (infinitive phrase–marked by “to.”)

~Verbal: beginning

~Type of verbal: gerundThe puppy, Charlie, wanted to play with everyone around him.

~Verbal: to play

~Type of verbal: infinitive

Thinking himself to be a regular Adonis, Jonathan soon found his pride to be his Achilles heel.

~Verbal: thinking

~Type of verbal: participle

Encouraged by the ovation, the conductor led the orchestra in an encore performance.

~Verbal: encouraged

~Type of verbal: participle

He will not allow the table to be moved.

~Verbal: to be moved

~Type of verbal: infinitive

are verb forms which are used as some other part of speech. The three verbals are participles, gerunds, and infinitives.

EX:

The *sleeping* baby breathed noisily. (participle–used as an adjective)

*Sleeping* is an essential part of maintaining the body’s health. (gerund–used as a noun)

I need to *sleep* now. (infinitive–used as a noun and marked by “to”)

T/F: The present participle form and the gerund form are identical.

T/F: A participle, a gerund, or an infinitive may be used as a noun substitute.

false; participle is an adjective

EX: *Because horses tend to be high-strung,* they must be treated gently.

“because” introduces an adverb clause and demonstrates a cause/effect relationship.

EX: *After* *the farmer finished harvesting the hay*, he stacked the bales in the barn.

The farmer stacked the bales in the barn *after he finished harvesting the hay.*An adverb clause that comes in front of the main clause (see above) is called the introductory adverb clause; it is set off from the main clause by a comma, and it modifies the verb.

The adverb clause tells much more than when, where, how, and how much. The following common subordinating conjunctions introduce adverb clauses and describe the relationship between the adverb clause and the main verb of the main clause or the entire main clause.

Time: when, whenever, before, after, since, while, until, as

EX: She went *before I could speak to her.*

Don’t talk *while you eat.*

You may come *when (whenever) you are ready.*

*While you’re waiting*, help me in the kitchen.

He called me *as I left the house.*

Manner: as, as if, as though

EX: They talk *as if (as though)* they have new information.

Make the salad *as I have taught you.*

Place: where, wherever

EX: We lived *where we could see Mt. St. Helens.*

I will go *wherever you say.*

Result: that, so that

EX: She was so early *that she helped set the table.*

He moved over *so that I could see better.*

Cause: because, since, as, for

EX: *Since we moved here*, I’ve no trouble with asthma.

She worked *because her father was out of a job.*

Purpose: that, in order that

Example:

Brave men have died *that America might live.*

They fought *in order that their wives and children could be free.*

Condition: if, in as much as, lest, in case, much as, provided that, on condition that, unless

EX: *If you’ve heard this story*, stop me.

I’ll come *provided that you’ll let me help.*

*If I were you*, I’d buy the house now.

*Much as I’d like to help*, I can’t.

*Lest anyone misunderstand*, I voted for the bill.

Concession: although, even though, though, even if

EX: *Although it is raining*, I will go.

*Even if I am late*, I’ll go in and sit down.

Comparison: than, as, as . . . as

EX: Work is more rewarding *than pleasure (is).*

Your essay is *as good as hers (is).*

Some adverb clauses can be shortened or changed slightly and still be adverb clauses.

EX: *If I were you* can be shortened to *were I you*;

*If you had told me earlier* can be shortened to *had you told me earlier*;

*When you leave* can become *once you leave.*

Adverb clauses can become *elliptical clauses* by simply eliminating the subject and auxiliary or auxiliaries. Such clauses must be used with caution.

EX: Adverb: Don’t change the horses *while you are crossing a stream.*

Elliptical: Don’t change horses *while crossing a stream.*

Adverb: A piano will deteriorate *if it is not played occasionally.*

Elliptical: A piano will deteriorate *if not played occasionally.*

Using Adverb Clauses as a Method of Subordination

The following example illustrates how an adverb clause can be used to combine sentences.

EX: Original sentences: Horses tend to be high-strung. Horses must be treated gently.

Combined sentence: Because horses tend to be high-strung, they must be treated gently.

The first sentence was reduced to a dependent clause with the addition of the subordinating conjunction. That dependent clause was then combined with the independent clause to form the sentence in the example above. Choice of subordinating conjunctions depends on the meaning relationship between the main and dependent clauses. Thus, changing the subordinating conjunction often changes the meaning of the sentence.

EX: *Because horses tend to be high-strung*, they must be treated gently.

*If horses tend to be high-strung*, they must be treated gently.

*Although horses tend to be high-strung*, they must be treated gently.

Normally, the adjective clause will come immediately after the noun or pronoun it modifies; only a prepositional phrase can come between the clause and the word it modifies. In the examples below, the adjective clauses are italicized.EX: The man or woman *who tries* will succeed.

The car *that I borrowed* is in good condition.

The fellow in the green jacket is the man *to whom I spoke.*

The subordinating words (in italics, above) that introduce adjective clauses and connect them to main clauses are classified in two groups:

Relative Pronouns: who, whose, whom, which, that

Note: who, whose, and whom are used in reference to people. Which is used in reference to animals or things. That can be used for either.

Relative Adverbs: when, where, why

In addition to introducing adjective clauses, relative pronouns function as noun substitutes. They function within adjective clauses as subjects, complements, or objects of prepositions. Relative adverbs function as modifiers.

Relative clauses are not difficult to locate in a sentence. Relative pronouns or adverbs are obvious signals. In addition, an adjective clause can be removed from a sentence, leaving a complete main clause, as the example below shows.

EX: The coat *that I am wearing* is my father’s.

If we remove the adjective clause, we are left with the following:

EX: The coat is my father’s. (complete main clause)

preposition such as to, for, in, into, or of, may be needed for the proper construction of the sentence. This preposition will precede the relative pronoun and will be considered as part of the adjective clause.

EX: She is the child for whom I am responsible.

Some adjective clauses are expressed without the introductory word. In such cases you can supply that or which and be assured that the clause is an adjective clause.

EX: The first car (that) Bob owned was a 1965 Chevy.

Adjective clauses may be *restrictive* or *nonrestrictive.* A restrictive clause is a clause which is necessary to identify or limit the possibilities to the thing that is meant. A nonrestrictive clause adds additional information but is not necessary to identify the thing that is meant. A nonrestrictive clause is set off from the rest of the sentence by commas.

Nonrestrictive: Dr. Ruskin, who took out Mother’s appendix, is speaking at our club this Tuesday.

Restrictive: The doctor who took out Mother’s appendix is speaking at our club Tuesday,

Dr. Ruskin is Dr. Ruskin whatever he does. Therefore, in the first sentence, we don’t need to know that he removed Mother’s appendix to know which doctor is speaking at the club. Since, however, the second sentence does not name the doctor to be speaking, the information in the adjective clause is necessary (or restrictive) to point out which doctor is speaking.

When a group of words is necessary, or restrictive, no commas surround it; when a group of words is not necessary, or nonrestrictive, commas surround it.

Restrictive: The girl who is leading the graduates down the aisle is my cousin.

Nonrestrictive: My cousin, who is leading the graduates down the aisle, is the valedictorian.

It usually takes the place of the subject, direct object, indirect object, predicate noun, or object of the preposition.

Subject: *Where I study* is my problem.

Direct Object: I wonder *what she sees in him.*

Predicate Noun: The fact is *that you promised to be there.*

Object of the Preposition: This plan is available *to whoever registers in time.*

Delayed Subject: It is fortunate *that you were in the building.* (*That you were in the building* is fortunate.)The following list includes most of the words which introduce noun clauses:

that, whether, if, what (subordinating conjunctions)

whoever, whomever, whatever, whichever (indefinite relative pronouns)

how, when, where, why (relative adverbs)

These words always stand near the beginning of the clause and signal a dependent clause; the relative pronouns and adverbs also serve some function within the clause. When that is the introductory word, it is sometimes not stated.

EX: I think (that) you are mistaken.

Indirect object

Subject compliment

Although an appositive gives the information another sentence might give, it does so with great economy of words. Because it does not restrict the meaning of the noun it renames, an appositive is set off by commas. Any noun can be followed by an appositive. An appositive phrase includes the appositive and its modifiers:-After a subject: Darrell, *the new superintendent*, called a meeting.

-After a direct object: We drove our new car, *a Saturn.*

-After a subject complement: I am Mary Trout, *your Avon lady.*

-After the Object of the Preposition: They came into Denver, *the mile-high city.*

Since an appositive is a noun, a noun clause or a gerund or an infinitive can be an appositive.

-Noun clause as an appositive: *Your statement, that the town is dying*, is not diplomatic.

-Gerund as an appositive: Sally’s newest hobby, photographing birds, is bringing her great satisfaction.

-Infinitive as an appositive: His idea, *to form a Norway Club*, will attract many people to this area.

~the famous etymologistHis mission, to climb Mt. McKinley, was yet to be accomplished.

~to climb Mt. McKinley

The building, a tall, gray structure, sat abandoned near the freeway.

~a tall, gray structure

She looked forward to her favorite activity, jogging on the beach, after she finished her work.

~jogging on the beach

When the child reached for his great grandmother’s candy dish, he remembered his mother’s instructions, that he should only choose one piece.

~that he should only choose one piece

It is not linked to the main clause by any conjunction or relative pronoun. The nominative absolute usually results when an adverb clause is reduced from clause to phrase level.Example:

Original sentence: *Because ideas proliferated abundantly*, the committee had a very successful meeting.

Nominative Absolute: *Ideas proliferating abundantly*, the committee had a very successful meeting.

Example:

Original sentence: *Since work was scarce*, most young people went to junior college.

Nominative Absolute: *Work being scarce*, most young people went to junior college.

In both sentences in the example above, the main verb of the adverb clause transforms into a present participle. Also, since, in this transformation, the adverb clause loses its “clause status,” the introductory words disappear.

Houses should be designed *to take advantage of the sun’s heat.* – infinitive phrase

My most valuable coin, *one from Spain*, is worth more than $100.00. – appositive

*The weather remaining turbulent*, we will postpone our canoe trip. – nominative absolute

The hero falls in love with a countess *who is very beautiful.* – adjective clause

*Although her personality had not changed at all*, Megan looked quite different. – adverb clause

Put the sizes on the uniforms *while sorting them out.* – elliptical clause

*By serving as a popcorn vendor*, Don saw many good games. – prepositional phrase with a gerund

We walked along the mountain path *looking for unusual flowers.* – present participial phrase

By mistake I opened a package *addressed to my sister.* – past participial phrase

*Headed by a senior*, the group drew up rules for School Spirit Week. – past participial phrase

The driver, *confused by the sign*, made a wrong turn. – past participial phrase

We hit a snag *while rowing to shore.* – elliptical clause

The play, *a three-act farce*, amused everyone. – appositive

Frances has plenty of time *to devote to her painting.* – infinitive

The two waiters exchanged a look *whose meaning was clear to me.* – adjective clause

*Even though Darla recommended the course*, I decided not to take it. – adverb clause

*Jumping across the ditch*, the fire threatened our house. – present participial phrase

*The fishing having become so poor*, we packed up camp and moved to another lake. – nominative absolute

*Whenever I can come* will be soon enough for the race. – noun clause

(useful when you don’t need a precise definition)

2. *Identify the Part of Speech* – By determining whether your unknown word functions as a noun, verb, adjective, or adverb, you move a long way toward figuring out its meaning. You can begin to see the word’s relationship to other words in the sentence.

3. *Pronounce the word* – Figuring out a word’s pronunciation is a big part of understanding what it might mean. Sometimes, reading the word out loud is enough to make you remember: “I’ve heard that word before.”

some writers use this form of *deduction*, in which a conclusion may be shown to logically follow from two or more premises. The letters in the forms listed below stand for nouns which are called *terms* of the syllogism. Statements are in one of four forms:

All A’s are B’s. (universal affirmative)

No A’s are B’s. (universal negative)

Some A’s are B’s. (particular affirmative)

Some A’s are not B’s. (particular negative)

One frequently heard advertisement states that nine out of ten Americans use toothpaste with fluoride to protect their teeth from decay. What about that tenth American? Surely, his teeth will all be filled with cavities.

The term bandwagon refers to the elaborately decorated wagon that carried the band in an old-time parade. Often these parades were associated with elections; therefore, to jump on the band wagon came to mean join the winning side. Presumably, those not on the bandwagon are losers. Since everyone wants to be a winner, being one who is not on the bandwagon may be difficult.

The bandwagon technique, however, may lead a person to make a decision for the wrong reason. A decision should never be based on the fact that everyone else is doing it. A good way to counteract bandwagon pressure is to ask yourself a couple of questions.

If everyone else were doing the opposite, what would I do? If no one else were around, what would I do? If your decision would be different because people around you were different, then you are probably being influenced by the pressure to conform and to jump on the bandwagon.

1. 000-099

2. 100- 199

3. 200-299

4. 300- 399

5. 400- 499

6. 500-599

7. 600-699

8. 700-799

9. 800-899

10. 900-999

11. F

12. B

2. Philosophy and Psychology

3. Religion

4. Social Sciences

5. Languages

6. Pure Sciences

7. Applied Sciences

8. Fine Arts and Recreation

9. Literature

10. History, Travel, Collected Biography

11. Fiction in English

12. Individual Biography

1. A

2. B

3. C-D

4. E-F

5. G

6. H

7. J

8. K

9. L

10. M

11. N

12. P

13. Q

14. R

15. S

16. T

17. U

18. V

19. Z

2. Philosophy, Psychology, Religion

3. History and Topography

4. America

5. Geography, Anthropology, Sports and Games

6. Social Sciences

7. Political Science

8. Law

9. Education

10. Music

11. Fine Arts

12. Language and Literature

13. Science

14. Medicine

15. Agriculture, Forestry

16. Engineering and Technology

17. Military Science

18. Naval Science

19. Bibliography

Larger indexes are themselves complete books or volumes. Some of these indexes list articles appearing in magazines or other publications that are issued periodically, whether weekly, monthly, or quarterly. One of the most widely used indexes is the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature.

The Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature indexes magazines written for the general reader. Whatever your subject, you will probably find something on it in the Readers’ Guide. These indexes are published in monthly or semi-monthly installments and are then combined in huge volumes, listing articles for a period of one or more years. In the front of the Readers’ Guide is an index to abbreviations as well as a list of all magazines referenced.

1. Internet – is made up of the computer equipment (including machines, wires, cables, and software) which connects millions of computers world wide. These interconnections form a net or web allowing a single computer to communicate with many other computers.2. software programs which run on computers connected to the Internet – These programs, known as information servers, deliver information requested by computer users connected to the Internet. Servers are thus information “holding tanks.” Some servers deliver information in the form of web pages while others provide menus of files to choose from. Some servers send and receive electronic mail (“e-mail”) messages. Nine different types of servers, each with its own function, are widely used today.

3. Internet web browser – a software program such as Firefox or Internet Explorer which specializes in accessing and displaying information on any or all of the information servers. Browsers are useful because they make searching for information on the Internet much easier, allowing those who have little experience with computers or computer languages to access information from several servers without having to learn the “language” required to operate each server.

1. a block of information stored in an HTML (Hyper Text Markup Language) file on a server

2. a “holding tank” for information on the Web or software which retrieves that information

3. the wires, cables, machines, and software connecting millions of computers world-wide

4. a device which categorizes and locates web sites

5. the table of contents of a web site

6. a software package which retrieves information from any or all available Internet servers

7. a highlighted word or phrase within a web page which acts as a “bridge” to another web page or site

8. a term which aids in narrowing a web search

9. an Internet discussion group on a particular topic

10. a collection of interrelated web pages united by a home page

1. web page

2. information server

3. the “Web”

4. search engine

5. home page

6. browser

7. hyperlink

8. keyword

9. newsgroup

10. web site

software

a browser

definition

cause-effect

contrast-comparison

classification-division

process analysis

EX: Some farmers seem to be able to predict the weather. For example, Old Mr. Beamish cocks his ear to determine the count of the crickets’ chirpings and knows that rain is coming.

When words like for *instance, for example, and by way of illustration* are used, the illustration-example is easy to identify. Notice that the general statement in the previous paragraph is followed by a specific example.

Another writing pattern that is seen repeatedly is definition. Like a dictionary, a definition exposition defines terms; however, where a definition in a dictionary is usually not even a sentence in length, an extended definition in exposition can go on for pages.

EX: The adjective indifferent is like a chameleon; it changes its color to fit the situation in which it is being used. It may mean “unbiased” when the reference implies partiality or impartiality. In such a case the indifferent attitude means that it simply does not matter one way or the other. The word may also mean that the case in hand calls for neither sanction nor condemnation in either observance or in neglect.

This particular definition could continue for several pages because the subject, the word “indifferent,” has many meanings. For complete clarification, every shade of meaning would have to be explored.

The cause-effect pattern is frequently seen in writings about events in history. The writer using this method attempts to show how one event or a series of events causes something else to come about.

EX: In 1914, Prince Franz Ferdinand–the crown prince of Austria–went with his wife on a visit to Serbia. At the time, the Austrian government had great influence over Serbia. This influence caused tensions with the Russians, who were also bent on controlling Serbia. While on the trip, Ferdinand was assassinated and killed by a group of Serbian nationalists who wanted independence from Austria. His death led to the Austrian government making very strong demands on Serbia. This circumstance heightened tensions with Russia whose support lie with the Serbs. Days later the First World War began with the Germans–who controlled Austria–declaring war on Russia.

The comparison-contrast pattern is used to show likenesses (comparison) or differences (contrast) of two or more subjects. In some instances both comparison and contrast will be used within one paragraph.

EX: In the fitness community, many people have trouble deciding between low-fat, low-calorie diets and high protein diets. Both are successful. When a person eats fewer calories than he burns, he will inevitably lose weight. This is the principle for the low-fat, low-calorie diet. Lower fat foods tend to have fewer calories (because fat has 9 calories per gram whereas protein and carbohydrates have 4 calories per gram), so sticking to low-fat foods helps a person cut calories. Fruits, vegetables, and whole grains are naturally low in fat.The high-protein diet, in contrast, focuses on protein as the building block for muscle. Muscle burns more calories than fat in the body and speeds up a person’s metabolism, which dictates how many calories she burns. The faster a person’s metabolism, the more calories burned. The low-fat, low-cal diet is a simple math solution: eat less than you burn and lose weight. The high protein diet is a bit more complex: eat to build muscle, burn more calories, and lose weight.

Writing of this kind usually announces the comparison or contrast at the very beginning. Such words as but, however, yet, moreover, and on the other hand signal this method.

EX: Golfers come in three types: the duffer, the amateur, and the professional. The duffer hits the dirt farther than the ball. The amateur hits the ball further than the dirt and then spends his time looking for the ball. And the professional inspires the others to come back and try again.

OR

EX: Three genres studied in Introduction to Literature are short story, poetry, and drama…Topic sentences such as the two above very distinctly indicate to the knowledgeable reader that a classification-division pattern of writing is forthcoming. Although the classification is easy to identify, the division is less easily spotted because it has already occurred. Golfers is a division of sports hobbyists. Literature is a division of the arts, which includes music and traditional arts such as painting and sculpture. Under the three genres a deeper classification will occur in the definition which will divide drama, for instance, into tragedy, comedy, morality plays, and the theater of the absurd.

The last category of exposition discussed here is process analysis. This kind of writing usually features an analysis or description of how to do something, whether that something is assembling a computer, operated a lawn mower, or otherwise completing a task. New equipment almost always includes a pamphlet which gives guidelines for use. In most every case, the pamphlet makes use of process analysis. Note that process analysis is implied in the title of the paragraph below: “How to Find the Perfect Gift.”EX: The first rule of gift-buying is to keep in mind the interests of the recipient. Too often, the shopper makes the mistake of buying a friend or family member the sort of gift that the buyer would like. Just because you enjoy tennis does not mean your non-athletic sister will love a top-of-the-line tennis racket. If you want to select the perfect gift, try to think of something that the recipient would love, but would never buy for herself. Maybe your mother has always wanted to get a manicure, but would feel silly spending the money on herself. Perhaps, you could present her with a gift certificate. Maybe your father loves baseball, but isn’t good at planning ahead to buy tickets. If that’s the case, buy a set of tickets and offer to join him. Remember, with gift-giving, it’s the thought that counts. Think about the recipient’s likes and dislikes and you can’t go wrong. If all else fails, you can’t go wrong with a gift-certificate.

Choose the type of paragraph below.

The best leaders are organized, efficient, and punctual. Molly Spencer, the President of the Spanish Club is just this type of leader. She keeps all of the club’s folders and rosters neatly arranged. She has organized several events to help students celebrate the Spanish language, and her fund-raisers have helped several students pay for Study Spanish Abroad programs. In addition, she’s never been late to a meeting. Molly Spencer is the perfect example of a leader

Choose the type of paragraph below.

W. Michael Blumenthal, a corporate CEO, talks about the mistakes he made in hiring:

“In choosing people for top positions, you have to make sure they have a clear sense of what is right and wrong, a willingness to be truthful, the courage to say what they think and to do what they think is right, even if the politics militate against that. This is the quality that should really be at the top. I was too often impressed by the intelligence and substantive knowledge of an individual and did not always pay enough attention to the question of how honest and courageous and good a person the individual really was.”

Click on the box to choose whether each sentence restates the key idea expressed in the key sentence.

Key Idea: When hot weather arrives and the nation takes to the outdoors, mishaps multiply.

DOES

Most people can learn to swim in ten short lessons.

DOES NOT

The majority of water-accident victims require mouth-to-mouth breathing.

DOES NOT

Heat exhaustion comes from overdoing in hot weather.

DOES

Dress in light-colored clothing to prevent heat strokes.

DOES NOT

An empty, tightly closed gallon jug will support a tired swimmer.

DOES NOT

Half of the summer deaths will occur on the highway.

DOES

First aid is to prevent accidents as well as assist in rescue.

DOES NOT

Bees, hornets, wasps, and yellow jackets sting more people in the summertime.

DOES

Outdoor and on-the-road eating increases the number of vacationing people stricken by food poisoning.

DOES

Click on the box to choose whether each sentence restates the key idea expressed in the key sentence.

Key Idea: Foresight often prevents disaster.

DOES

Difficult times disappear if people prepare for them.

DOES NOT

Planting and harvesting in summer provide food for the winter.

DOES

Poor planning is a result of laziness.

DOES NOT

Disasters sometimes happen even if people plan for them.

DOES NOT

Some crises can be avoided if they are anticipated.

DOES

Disasters often teach people to plan ahead.

DOES NOT

Planning ahead often brings about suffering.

DOES NOT

Click on the box to choose whether each sentence restates the key idea expressed in the key sentence.

Key idea: It is sometimes necessary to adjust yourself to those who fail to adjust to you.

DOES NOT

Animals are required to adjust their living patterns to their environment.

DOES

People often find it necessary to make adjustments in their lives because others won’t.

DOES

We should treat others like we would want to be treated.

DOES NOT

Some people refuse to change.

DOES NOT

Others’ refusal to change for us may mean that we must change for them.

DOES